In the past 2 years, my husband and I have traveled to 40+ countries. As a traveler suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), I take careful note of the bathroom facilities around me. Dealing with IBS forced me to pay attention to toilets around the world.

From using water over toilet paper, to pipes that cannot handle anything but bodily waste, to open defecation, cultures and countries can vary drastically in how they do their business.

In this article, I cover my firsthand experience of pooping around the world—and discuss some sustainable toilet practices that protect our ecosystem.

How much do you think about how you poop?

First Flush Toilet in North America.

Newfoundland, Canada

According to the World Health Organization, 2 billion people worldwide do not have access to basic sanitation facilities such as toilets or latrines. Of these, 673 million defecate in the open. Open defecation includes gutters, bushes, and open bodies of water.

Defecating in open water has been going on forever. In 2015, my husband and I visited Newfoundland, Canada. There’s an archaeological site where the Colony of Avalon was started in 1624. Here, close to the harbor, is a toilet build out of stones.

The chamber of the toilet had an outlet directly to the sea. At high tide, the water rose and filled the chamber halfway. At low tide, the matter in the chamber washed out to sea.

Shit Rivers

Large contaminated bodies of water can make huge numbers of people sick. In our travels, we have seen numerous rivers that I call “shit rivers.”

Shit river on a Cambodian island.

Shit rivers are run-off from homes, businesses and hotels that typically line the busy street in booming tourist areas in some poorer countries—areas that don’t have sound solutions for proper disposal of waste.

If the odd color of the water doesn’t give away the presence of a shit river, the smell soon will.

Often, the river of shit starts in the town and empties in the ocean. We’ve seen them in India, Indonesia, Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador.

The shit river isn’t new either.

The river Thames in London, England was so contaminated during the 19th century that four major outbreaks of cholera between 1832 and 1866 led to the death of tens of thousands of people.

Today, the threat of cholera in developed countries is low. In the world’s poorest locations, Cholera kills an estimated 143,000 people each year.

Controlling the spread of bacteria

While traveling, I have gotten dysentery in Columbia, food poisoning twice in Peru, and once more in India. My husband also got food poisoning in Peru, Egypt, and Indonesia.

Pre-cut fruit may be washed with unclean hands or unclean water

What causes diseases like dysentery? Ingesting fecal matter (poop). Generally, this occurs from eating food prepared with unwashed hands or drinking contaminated water.

Gross.

How does fecal matter make its way into water or food?

Traveling through northern India, we side-stepped piles of poop in the streets. We saw children pooping on busy streets in Indonesia.

These piles get covered in flies.

The flies make their way to the restaurants where people prepare food. Flies land on the food. We eat the food.

Or, food is handled by a person who hasn’t washed (or hasn’t properly washed) his or her hands.

Water gets contaminated when fecal matter is too close to a water source, and then someone ingests the water. This can come from drinking contaminated water or eating fruit or vegetables washed with contaminated water.

Bacterium causing diseases like dysentery and cholera are containable. But the World Health Organization reports that diarrheal disease is the second leading cause of death in children under five years old, and is responsible for killing approximately 500,000 children every year.

Heavy tourism and toilets

Cute backcountry photo. But did you poop sustainably?

In Peru, we visited a remote area of the Amazon. We went several miles downriver to visit a macaw clay-lick, where the animals gather to ingest needed salt. The Tambopata Reserve holds the highest concentration of avian clay licks in the world. As such, this area is popular with tourists. Tours to visit the clay lick start at 5 am. While waiting for the macaws, a light breakfast is served.

We ate. We had coffee. We had to poop.

We ALL had to poop.

The guide instructed us that if we needed the bathroom, there was a trail. Walk down. Find yourself a spot.

Ours was a group of 9. There were at least 5 other groups of similar size there with us, and more to arrive throughout the day. Yikes.

What we experienced in the Amazon is common at popular tourist attractions worldwide. When tourism expands at a rapid pace, it can be difficult to keep up with providing enough sanitary facilities to accommodate the growth.

A sign we encountered at a New Zealand campsite.

Even in modern countries like New Zealand, booming tourism is bumping up against the capacity of public bathrooms at popular sites. Following Lord of The Rings popularity, word got out about the country’s stunning scenery. After the movie’s release in 2001, tourism in New Zealand increased by 50%. The country has seen even more increases in tourism since then. A lack of sanitation facilities has left many of the country’s campsites covered in poop and toilet tissue.

When we visited, we were surprised by the number of aggressive signs posted in heavily used areas intended to remind campers to keep the surrounding environment clean. Water quality in New Zealand was once one of the world’s cleanest. New Zealand’s system of rivers and lakes are now some of the most polluted among OECD countries. Over tourism happens in obvious places—and in somewhat non-obvious places thanks to social media. In Australia, a boat house popularized by Instagram received so many tourists that the city of Perth spent $278k to construct a public toilet along a remote stretch of highway.

Developing sanitary systems in remote areas that allow for sustainable and responsible tourism, but do not disturb the surrounding wildlife, disrupt the life of inhabitants, or pollute the waterways is complicated.

Water over toilet paper as a cleaning method

In many countries, people use water to clean themselves after using the toilet instead of toilet paper. Exactly how water is used depends on the country.

In Japan, the bidet has been popular for many years and the technology when it comes to the toilet experience is impressive.

You can warm your toilet seat, dry after you use the bidet, adjust water pressure, or play music if you are feeling shy about the sounds of the bathroom experience.

In the Indonesian countryside, it’s a little more primitive. You squat. The right-hand scoops water from a bucket into the left-hand. The left-hand is the hand you use to clean yourself.

A bucket of water is often used to flush the toilet. We observed this method in many countries, including Peru, Cambodia, and Madagascar. In some countries, especially in places with lots of foreigners, you can find multiple types of toilets in the public bathrooms.

Protecting piping systems

In places where water is used for cleaning instead of paper, the plumbing isn’t built to handle toilet paper.

Signs all over the world instruct users to throw paper in the bins provided.

In the Western world, our pipes have been built to manage toilet paper—just don’t dispose of wet wipes in there.

Gender separation

Ever wondered whether there are separate bathrooms for men and women all over the world?

Yup, turns out there are. Separate bathrooms for men and women seem to be a universal feature of bathrooms in the developed and developing world. Very rarely do we see unisex bathrooms.

Solutions and the Manavta Project

There are no perfect answers when it comes to creating the best the sanitation facilities worldwide. It’s complicated.

But it’s important we try. That’s what my friend Nabeel Jaffer is doing with his non-profit, The Manavta Project.

We met Nabeel while traveling in Egypt and immediately bonded over sanitation policy (weird, I know). Manavta empowers leaders to bring safe sanitation to their communities through education.

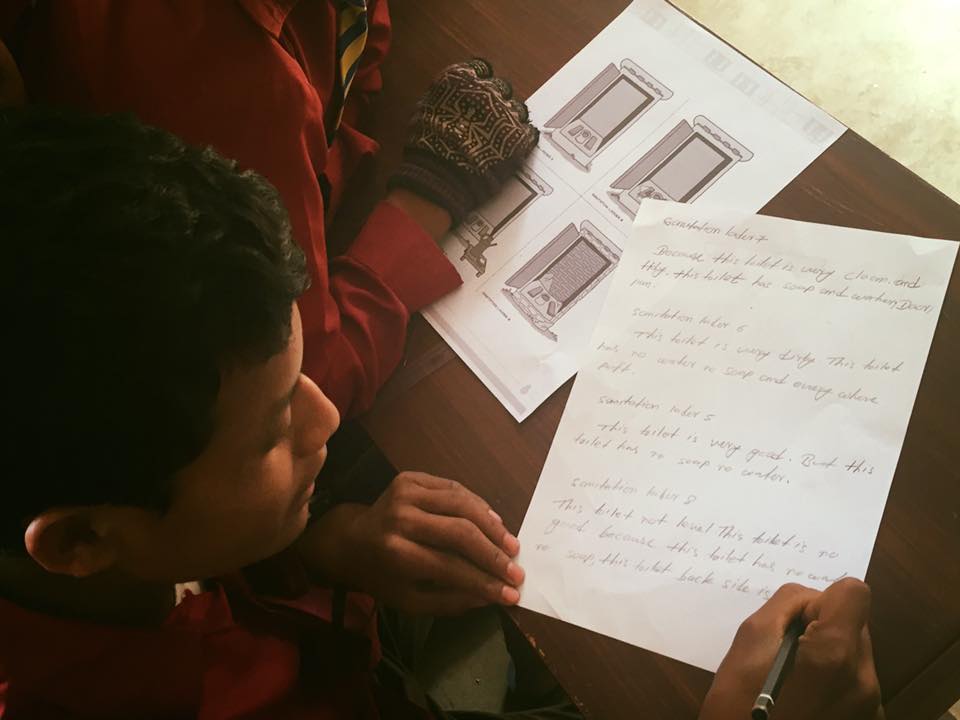

Manavta is focused on building toilets for poor communities in Nepal. Manavta’s first project was at a school in Nuwakot Nepal (a little outside of Kathmandu). They built a toilet for around 100 people. It was built specifically at the school to model sanitation for the community.

The second was a post-earthquake project in Sindhupalchowk, Nepal (the epicenter of the 2015 earthquake). Three EcoSans toilets were built and are currently being used by around 7 families (50 people).

EcoSan toilets are closed systems that do not require the use of water, and recycle nutrients to create resources for agriculture. EcoSan toilets may be an answer to minimal environmental impact in many areas of the world.

Manavta plans to scale up in installations of these EcoSan toilets as the communities have found urine quite useful for farming. You can learn about these projects at https://www.manavtaproject.org/projectjholunge.

Ending thoughts

Having more toilets available in countries like Nepal with proper disposal of waste will go a long way in protecting our fragile ecosystem and preventing the spread of disease. Diarrhea is a nuisance for me with IBS—it shouldn’t be a death sentence for those without access to proper sanitation.

People are “going to go” whether they have proper sanitation or not. If a toilet isn’t available, a person will find one. Maybe it’s a street. Maybe it’s a spot on a trail. Maybe it’s the ocean.

Between feces, chicken feet, wet wipes, trash, and shit rivers, I think the environment could really use a break. Projects like Manavta are paving the way for greater access to sanitary facilities for some of the world’s poorest people.

For tips on leave-no-trace pooping methods, check out: https://overlandsite.com/overlanding/how-to-poop-outdoors/ by Ferenc from OverlandSite.